Campaigners,

take heart! You needn’t spend the whole weekend sitting in a mud puddle

because you didn’t bring your shelter-half along (unless you really want

to). You have options, but they involve teamwork and cooperation (not to

mention minty fresh breath).

What

you need are two or three like-minded pards, a large knife or camp ax,

and the time to put the plan into action (about eight man-hours). A ten

to fifteen foot length of rope would be nice, but not essential.

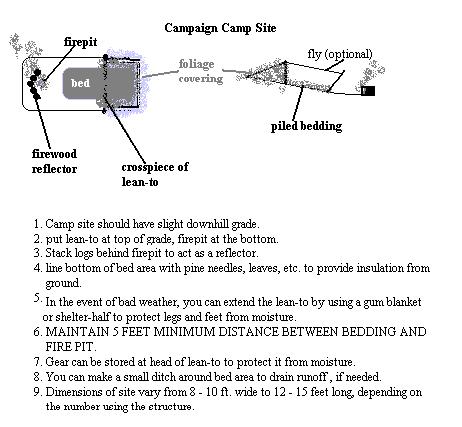

Begin

by clearing an area about ten feet wide by fifteen feet long. The ideal

site, described here, will have two trees or fence posts about ten feet

apart on one end of the plot. Try to set up on the lee side of a hill,

out of any obvious runoff or areas of ponding. You want to remove any large

sticks and rocks, and make sure you haven’t located the residence of any

stinging or poisonous life forms. A slight slope is better than level

ground.

Next,

you want to string your rope across the two uprights, about three and a

half to four feet above the ground. You can use a suitable length of wood

for the same purpose, but you do need the cross piece. Meanwhile, one of

your pards is off cutting down branches or other suitable foliage, about

four to five feet in length. You need a lot of these, so don’t bother the

worker bee with other tasks. He’s plenty busy.

While

you’re waiting for the shrubbery, go to the other end of the plot and prepare

your fire pit. You need a shallow depression, no more than four inches

deep. When you’re done, help your bunkies gather firewood (they should

already be doing this). Gather any dry wood you can find, preferably stuff

that has been down long enough to turn grayish. This is seasoned wood,

and will burn more easily and produce more heat than green wood. Stack

the wood on the side opposite the shelter end of your plot (i.e., behind

the fire pit.)

By

this time, there should be enough foliage in camp to begin constructing

the lean-to. The secret to making the lean-to water resistant is layering.

The first layer rests against the cross piece, and also covers the two

sides of the lean-to, leaving the side facing the fire pit open. The next

layer must overlap the first to cover as many openings as possible. The

third layer should cover any remaining holes. If needed, add a fourth or

fifth layer. If you are expecting rain, you can place a gum blanket on

top of the lean-to to provide more shelter from the elements, and

you can extend the sides and top a few feet to provide more dry area forward.

You must maintain a minimum of five feet of clear area between your fire

and your sleeping area, more if there is a wind that keeps changing direction,

so that embers and sparks from the fire do not ignite you or your weekend

palace.

For

the entire sleeping area, you will want to put about four or five inches

of dry leaves, pine needles, straw, or grass down for insulation. You will

want to do this even in summer, as it keeps the chill of the ground away.

Over this, you can place a gum blanket or a blanket, as a sort of

“mattress cover”. Now you can place the bedrolls up under the lean-to to

keep them out of the weather.

At

dusk, make your fire for the night by starting a small fire and keeping

it small. This fire will keep your feet warm, and drive away any dew that

may form. You can increase the effectiveness of the fire by standing up

pieces of wood behind the fire pit as a sort of reflector, directing the

heat toward the lean-to. It also helps keep the wind from blowing embers

about. The reflector should be no closer than two feet to the fire, and

ideally it should be further from the fire than the length of the tallest

piece of the reflector wall.

Take

a few pieces of wood and lay them up by the lean-to, to keep them out of

the weather. That way, you will have dry wood to start the fire next day.

Use your gum blankets to cover the parts of your blankets that project

beyond the cover of the shelter. The unused headspace in your shelter makes

a good place to stow gear like your muskets and such. Do not store food

in your shelter, as creatures of the night may not be concerned about disturbing

your sleep if they smell a Snickers bar or can of tuna fish.

When

the event is over, take some time to disassemble your shanty, spread things

about the site, and make certain your fire is soaked and stirred well,

and pack your trash out (Well, thank you, Ranger Rick).

Oh,

yeah, about the minty fresh breath: Could you sleep next to someone with

stale cheese breath? Didn’t think so. I mean, there’s authentic, and then

there’s just disgusting…